A bigger emphasis on Shakespeare and British History

Thousands of teenagers across the country have started their GCSE exams. 2019 is the third year in which candidates will be sitting what we call the ‘new’ GCSEs, the first ever new GCSEs were sat in 2017. So what are the ‘new’ GCSEs, and how do they differ from the ‘old’ ones?

The new GCSE format was introduced as a part of a broad programme of reforms in secondary school teaching and qualifications undertaken by the then Education Secretary Michael Gove in 2014, and included the following changes:

1. Less coursework than before, with only some of the more practical subjects like Dance, Art and Drama containing this element of assessment

2. Introduction of final exams, with grades in almost all subjects depending on exams taken after two years of study, rather than in modules with exams along the way.

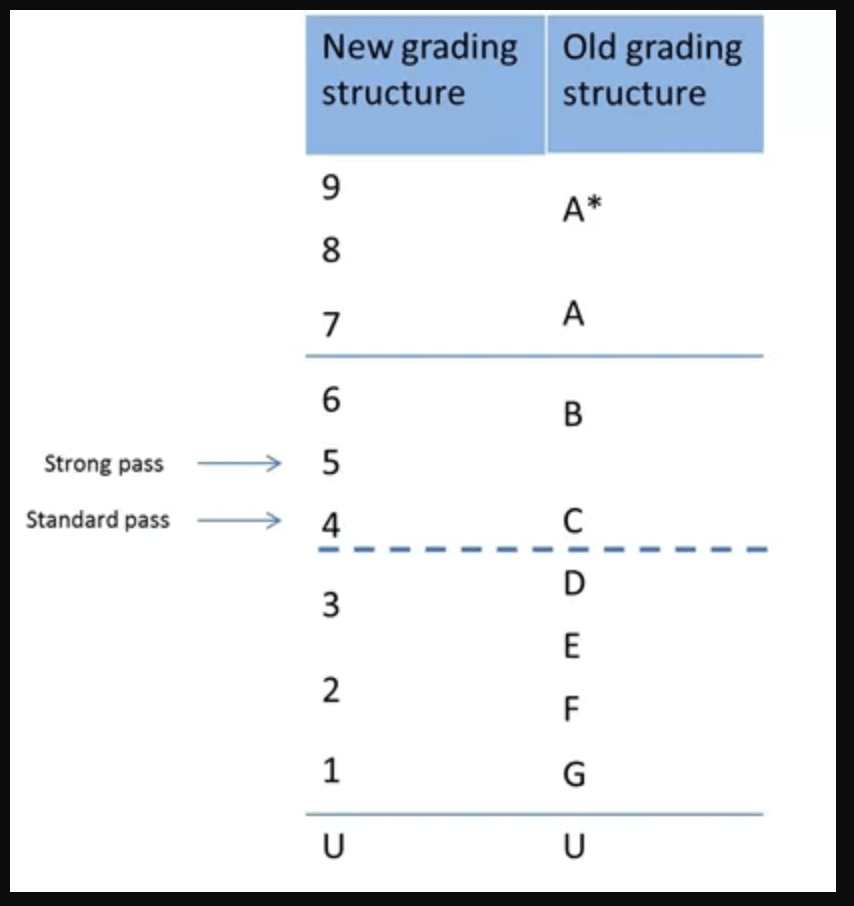

3. There is a new 9 to 1 grading system, which aims to better differentiate between the highest performing pupils and distinguish clearly between the new and old exams. It has more grades at the higher end to recognise the very highest achievers. Grade 9 is the highest grade and will be awarded to fewer pupils than the current A*. Grade 4 is a ‘standard pass’, this is the minimum level that pupils need to reach in English and maths (previously a ‘C’). If pupils fail to achieve a grade 4 or higher, they will need to continue to study these subjects as part of their post-16 education. There is no re-take requirement for other subjects.

The reforms came as part of a government drive to improve schools’, pupils’ and employers’ confidence in the qualifications, ensuring that young people have the knowledge and skills needed to go on to further study and work. According to Michael Gove, the goal was to pitch the content of the revised examinations at a more sophisticated level than the old GCSEs, especially in sciences and maths.

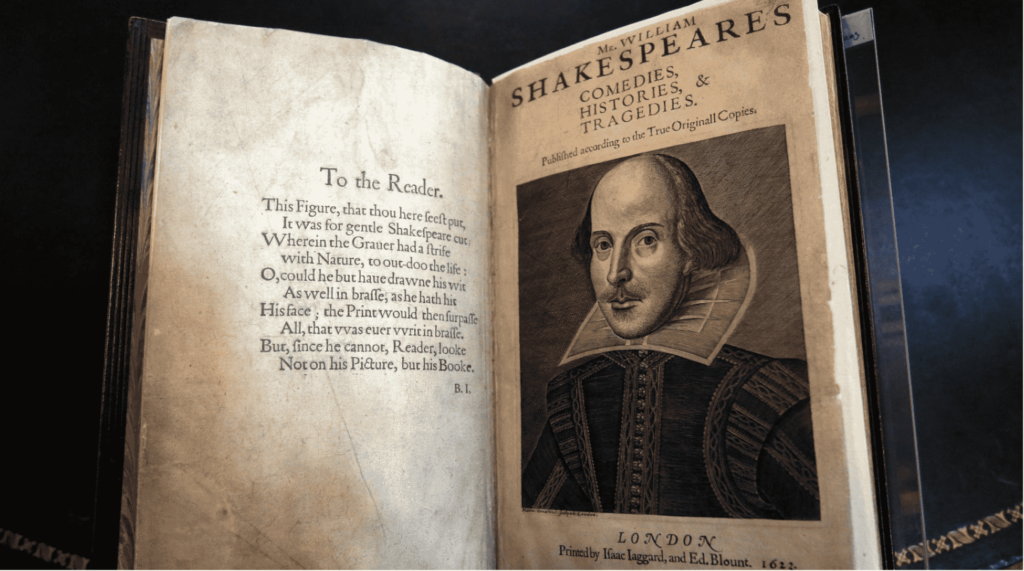

“By making GCSEs more demanding, more fulfilling and more stretching, we can give our young people the broad, deep and balanced education which will equip them to win in the global race,” Gove told the House of Commons when unveiling the new reforms. A lot of it makes sense. In English literature, for example, students are now required to study at least one full Shakespeare play, as opposed to extracts. For those studying history, substantial elements of British history constitute a minimum of 40% of the syllabus.

However, the introduction of the new GCSE exam structure was met with a degree of criticism. Some educationalists were concerned that making exams harder does not guarantee higher standards nor mean that students will be prepared for a job. By the same token, many argued that education can only be improved by more emphasis on individual-focused classes to help students grow, whereas making exams harder would only alienate introverted or troubled students. It is true that the first students taking the new exam experienced high levels of stress and anxiety. But some tweaking was done, strategies improved, and after the initial hiccups, the pressure is easing, the schools and students alike settling into the new exams. This year, everyone is more familiar with what is expected of them. The only issue remaining, as will all exams, is how to best prepare for them.