Last week was Mental Health Awareness week, which highlighted yet again that mental health problems amongst young people are on the rise – stress, anxiety, panic attacks, self-harm, depression and eating disorders are on the increase. As a result, educationalists are searching for new ways of helping young people under pressure. A new route being explored more and more is the connection with … DOGS.

There has always been a special bond between humans and animals, especially dogs. The bond was somewhat dampened in the seventies, when extensive press coverage of health hazards associated with dogs, first in the United States and later in Britain, lead to a growing anti-dog movement in the media and had a damaging effect on public perception of dogs and their owners. One of the first to challenge that perception was the charity Pro Dog; founded in 1976, it set out to highlight the beneficial influence of dogs. The charity gathered a panel of veterinarian and medical experts to respond to health scares; it also organised campaigns against restrictive laws on dogs and worked towards the abolition of the dog licence, which was eventually scrapped in 1988.

Since then, dogs have been allowed in – first cautiously, then more and more open-heartedly. Today, one can see dogs in nursing homes, hospitals and in workplaces. What about schools? A few months ago, the University of Buckingham organised a conference to examine how to respond to the stresses and anxieties facing young people. Speaking at the conference, Sir Anthony Seldon, the former headmaster of Wellington College and a longstanding advocate of the need for schools and universities to pay more attention to mental health, said that every school should have a dog to reduce stress in the classroom. “The quickest and biggest hit that we can make to improve mental health in our schools,” Sir Anthony said, “is to have at least one dog in every single school in the country.” His words were echoed by the Education Secretary Damian Hinds, who noted that more and more schools seem to have what he called “wellbeing dogs”.

It is well know that when children are hurt or anxious or sad, they can relate to animals in a way they can’t with human beings. Indeed, having dogs at schools is both powerful and cost-effective. When dogs are present, children feel more relaxed. In many schools dogs are integrated into the educational process, they help to enhance learning and encourage creativity. In one UK school, a dog is brought in to read with the children. The dog’s ability to respond to commands on flash cards encourages the children develop their literary skills.

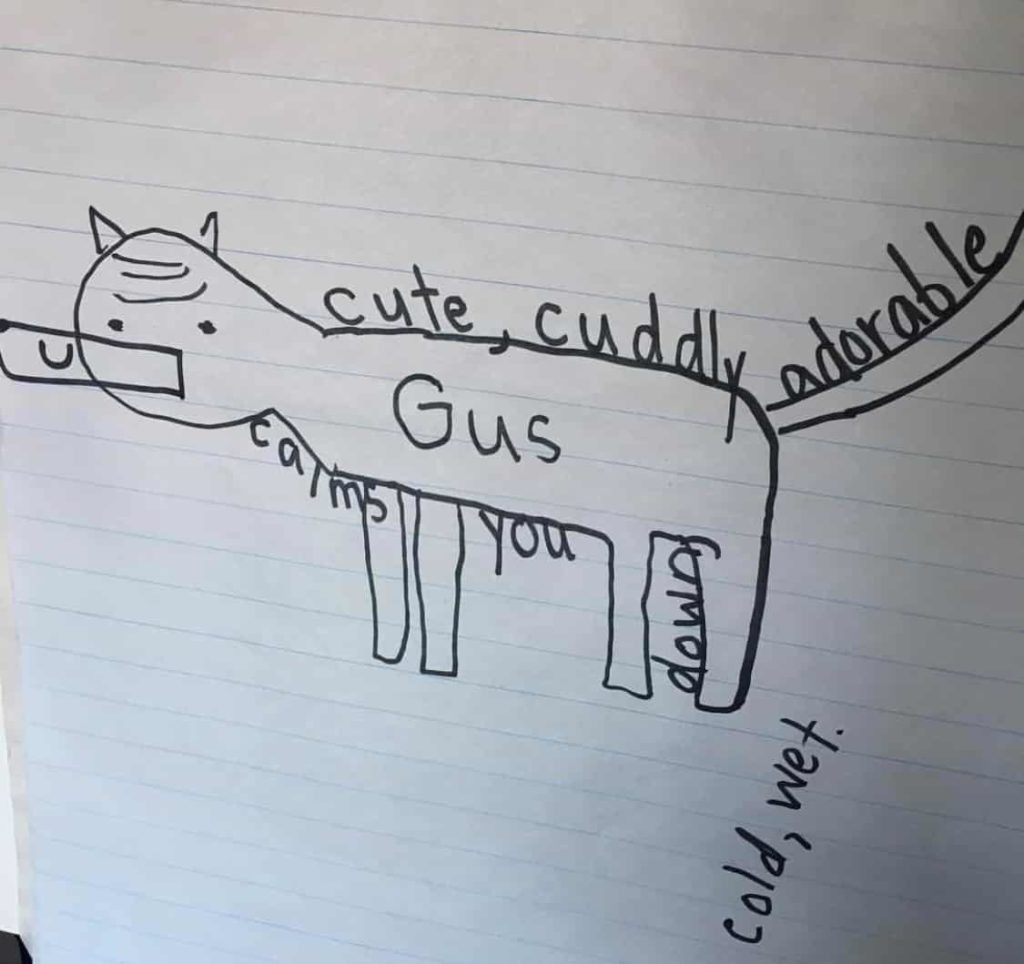

In another school, a dog called Gus is an object of class discussions and is often immortalised in art.

In yet another school, a pioneering approach was developed in teaching teenage boys who have been excluded from mainstream education: the school has no uniforms, no detentions, and no punishments – but does have a dog, which has a calming effect and helps to bring barriers down in the school.

Similarly, therapy dog sessions are becoming more popular on university campuses. In the study published in the journal ‘Stress and Health’, researchers surveyed 246 students before and after they spent time in a drop-in therapy dog session. The study has found that when students are allowed to cuddle therapy dogs, their stress levels plummet, and energy and happiness increase. Encouraged by the findings, Leeds City College acquired a cockapoo. Five Labradors have joined the staff of Middlesex University to help students with exam stress and those whose anxiety puts them at risk of dropping out. Other universities have followed suit.

Having therapy dogs on campus is cheap — much cheaper than hiring extra counsellors or treating stress-induced disorders at medical clinics; dogs have a measurable, positive effect on the wellbeing of students: the simple act of petting a dog is shown to reduce blood pressure, lower levels of stress hormones, like cortisol, and increase oxytocin, all of which contribute to respiratory and cardiovascular health.

To make sure there is no danger, therapy dogs are carefully selected. The most important characteristic of a therapy dog is its temperament. A therapy dog’s primary duty is to make affectionate contact with unfamiliar people in sometimes-stressful environments. A good therapy dog is friendly, confident, gentle in all situations and must be comfortable and contented with being petted and handled, sometimes clumsily. They must have a calm and stable temperament and able to tolerate children, crowded public places and other stressful situations, without becoming distressed or dangerous.

From helping young children read to relieving the intense stress faced by university students, dogs are an increasingly familiar part of educational programs across the country.

P.S. Two cocker spaniels, Poppie and Daisy featured in the blog, are Gabbitas’ own.